by #LizPublika

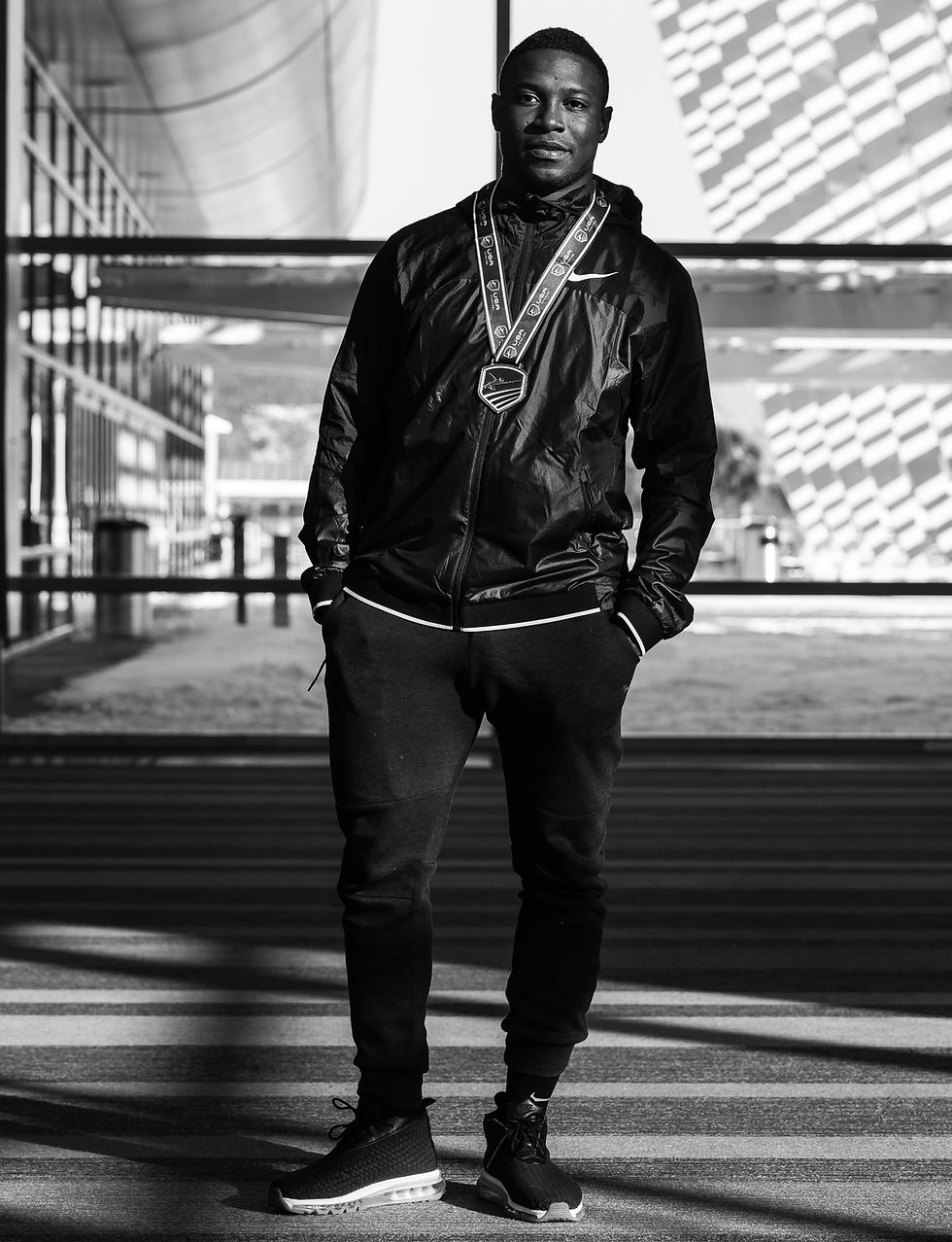

During the 2016 Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro, three-time Olympian Daryl Homer won a historic silver medal in men's saber fencing, thereby becoming the first U.S. medalist in men's saber since Peter Westbrook won a bronze medal in 1984 as well as the first U.S. men's silver medalist since Chicagoan William Grebe in 1904. That’s pretty impressive, considering that no American has ever won a gold in men’s individual saber.

The accomplished athlete was born on St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, and — at the age of five — moved to an apartment in the Bronx with his mother and younger sister D’Meca. He started fencing at the age of 11, after coming across a picture of a masked fencer in the dictionary and finding it "very cool," so joined the Peter Westbrook Foundation in NYC, a program dedicated to exposing inner city youth to fencing, and chose saber because that’s what Westbrook chose.

His talent for the sport was noted from the get go and began working with (now seven-time) Olympic coach Yury Gelman immediately, winning a bronze medal at the 2007 Cadet World Fencing Championships, and another bronze at the 2009 Junior World Championships in Belfast. That same year he competed in his first senior World Championships in Antalya, finishing 23rd, and took the NCAA title as a sophomore. Other victories followed.

Shortly after his Olympic silver medal, he left long-time coach Yury Gelman and the Manhattan Fencing Center for another coach. To date, Homer has competed in the 2012 London Olympic Games, the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games, and the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games. In the spring of 2023, the saber-fencer suffered a serious injury which derailed his plans from making it to the Paris Olympics in 2024, but that doesn’t mean Homer is ready to put his weapon down.

Aside from vigorously training post injury, Homer takes time to speak to inner city youth about balancing his career with his athletic passions. He is a brand ambassador at Fencing in the Schools, a non-profit that aims to enrich the lives of students in the inner city through fencing by focusing on its health benefits, life skills, and exposure fencing can provide. He’s realistic about his experiences and aims to inspire kids to pursue their dreams through discipline and respect.

ARTpublika Magazine had a chance to speak with Daryl Homer about his love of fencing, what it takes to win, and how to recover from unexpected setbacks.

You recently got back from the national championships in Italy. Did you get to spend a little bit of time at home?

I actually just got home from vacation. I was in the Virgin Islands, that’s where I was born, so it was nice to spend time with my grandmother, be on the beach, and relax.

What have you been up to as of late?

A ton. A lot of competing, for sure, and exploring a lot of personal interests, like doing my own storytelling. I am doing work around the world and spreading fencing to marginalized communities. I also represent the Peter West Foundation, which has been a lifeline for me, so I have the opportunity to mentor the next generation.

The 2012 Olympics were your first, what did you do after?

I came back, finished school (St. John’s University) and started working at an advertising agency, where I spent around three years.

Are you still working in advertising?

I’m not currently in advertising, actually. But at the time, I worked as an account person at an agency, doing a lot of work around culture and sport, which was a really, really amazing experience. In fact, I think that experience really allowed me to work pretty seamlessly with brands today; I work with a couple of brands in the capacity of telling my own story, which is really awesome.

When you came back from the Olympics, you did so with a new status. How did that experience help you on your road to becoming a mentor for other kids?

I think it happened organically. Thank you for saying that it was “a new status,” but things felt oddly normal. I went back and finished college and then got a 9 to 5 job; so, overall it felt pretty normal. But, I think that it cemented the fact that I had figured out, in some capacity, how to put my mind toward being successful at something, and I think that that is something many others want to learn more about. I do think that I came back with a platform that allows me to share those experiences. I am just trying to pay it forward.

In previous interviews, you’ve stated that you cannot fence if you cannot control your emotions. So, going to your second Olympics, was it easier or harder to control your emotions, and why?

I had every possibility to stop fencing after the 2012 Olympics. I’ve also reached my goal, which was to make it to the Olympics team, where I performed well. I was 22 at the time and could have easily segwayed into a corporate career. But, I think that after 2012, I was motivated and I knew that fencing was still something that was really important to me and there was still more to accomplish.

Did you feel the same way after 2016?

I’d say that there was more pressure after the 2016 Olympics where I medalled, and I felt like: OK, I really want to do this again. I really want to repeat this. I want to do more of this. There were still so many things I didn’t accomplish in the 2012 Olympic Games.

After you’ve won a medal and achieved all that you have achieved, what keeps you coming back?

I don’t think that I have reached my full potential in this sport. And the things that I have experienced, I want to experience them over and over and over again. It’s not even about the medal, I just want to feel like I have reached my full potential, that’s all I’m saying.

With age comes wisdom and experience. How do you feel about your fencing at this point in your career?

I think that something I’ve had to come to terms with recently is, when I watch videos of myself when I was younger, I think: Agh! I was so explosive, I want to get back to that. But I realize that, and I think every athlete realizes this, there is a shift that happens later in your career.

For example, when you look at videos of young Kobe Bryant, he’s dunking over everyone. But later in his career, he’s picking his spots more carefully and he’s jump shooting. So, I think there’s a shift that happened for me — in the last 4, 5 to 6 months — where I started thinking about this.

Because I’m seeing younger athletes doing what I want to be doing, I remember myself doing the same when I was younger. But, with this shift you realize that your wisdom and your intelligence and your experience are really what should be guiding you at this stage.

That’s been echoed by other fencers, who have stated that the sport is about strategy.

I think that’s 100% true but the really powerful thing about fencing is that everyone can choose to make their strategy whatever they want to make it. So, there are people who want to make fencing hyper physical, and that’s OK; there are those who want to make it more cerebral, and that’s OK; and then there are people who want to fence but not be as strategic. So, there are many different ways to approach the game. I tend to approach it, at my best, with a combination of strategy, creativity, and coordination.

How do people in your family support your endeavors?

My family has always been immensely supportive. And it’s easy to support someone when things are good, but it’s so much more important during the hard moments. It helps having people to turn to. Both my blood family and my fencing family completely support me at all moments of my career, and that’s really important to me.

So, in 2016, you brought home the silver medal. How did you do it?

Leading up to 2016, I was in a pretty good training rhythm, which definitely helps. You have to put in a lot of hard work, hope for a little luck, and have a lot of belief in yourself. All of those things came together on that day, while also being strong, being fierce, being courageous and being creative. It was super beautiful and it’s something you want to repeat, beat, but also acknowledge in that moment in time. You have to savor that at that time.

Can you tell us about your routine on competition day?

I try to make competition day like any other day. In the morning, I’ll usually take a shower to ensure that all my senses are awake. I’ll make time to decompress, but I am very task driven so I’ll think about having a lite breakfast for good fuel; I’ll make sure to arrive at the venue two hours before, so that I have enough time to get there and relax without having to jump into my warm up. Then I’ll get warmed up one-on-one with my coach, or do some drilling, or get in some footwork. And then it’ll be just headphones on, getting locked in, and getting ready to go.

When you speak to your coach, what advice do you normally get?

I think the main thing is to believe in myself. Anything is possible in these competitions and if I’m not 100% confident in what I am doing, things can easily turn against me. So the main thing is to believe in myself and know that I’ve done the work, so I have to just be completely present in the competition.

And are you able to achieve this state regularly and easily?

I am constantly trying to search for ways to be more consistent in that, because it doesn’t always work the way I want it to, for sure.

Do you have a strategy for calming your mind? Or is it more like compartmentalization until you are able to process your thoughts and emotions after the fact?

I think that there is a healthy amount of that, but also a good amount of meditation before I’m even in the competition setting. I am able to understand the emotions that may come up before they do come up. I try to visualize the whole match, the warm up before the tournament, the match, the emotions I’m going to feel, sometimes even the reactions of the audience in the room after competing, because that’s really important to me. I think another thing is sitting quietly and in peace. So much of this stuff is in your head, so it’s really nice to just sit and completely clear your mind.

What was it like to emerge victorious?

The Olympic games are a special tournament, because of the crescendo effects. I still remember our team gear processing and the flight. And then we get to Rio and think: Wow, this is amazing! The Olympic village is there and everything starts to feel more real. Then there’s the opening ceremony that pumps the athletes up.

You start watching your friends compete and think: OK, my turn is finally coming soon. Then it’s your turn and it hits: I’m really here now. At that point you just have fun competing.

You’ve been to so many championships, do the Olympics feel on par with those events or is this historic event in a league of its own?

The Olympics are way bigger! Way bigger. Not even comparable.

So, in 2020, how was your Olympic experience different from the ones before?

Those were the Covid Games. Everything was quiet, it didn’t feel like the real games. There were no fans, no arena; it was a completely, completely, completely different experience.

Since you mentioned that the energy in the room is important to you, how was that experience?

It was very hard, unfortunately I didn’t feel like I got the most out of those Olympic games. I was very grateful that it wasn't my first time, but it was definitely a tough experience — not what I imagined. But a lot of pressure was lifted off of me after those games. I realized that I wanted to fence the way I wanted to fence in my career, and that I could live with that, and I think that was a bit strange for me.

What does fencing mean to you?

Fencing is my first love. I became the person that I am today through this sport, I learned to manage my emotions through this sport. I gained confidence through this sport. I became a better student because of this sport. I am speaking to you now, because of this sport. It is something that has been amazingly formative of my character and is such a big part of who I am that I don't know who I’d be without it. It’s something that I’ve sacrificed more for than anyone or anything before.

So, you work with some seriously major brands: Toyota, Polo Ralph Lauren, and Lululemon. How did those partnerships come about? Do you like modeling?

I don’t know if I love modeling. But, I think that I have an eye towards branding and an eye towards storytelling, and that’s a lot of what I’ve done. We work on a lot of different things, but they help me contextualize different parts of my training or my journey within the brand. And it’s something that has been very helpful, since fencing is not a big money making sport. So it’s been great to have a way to monetize it. I get to build a portfolio for things I want to do later in life.

Which are?

Branding, working with athletes, storytelling around talent — really telling stories about the art represented and highlighting those stories. I think that I’d like to start my own business, but I am not against working for someone else before that.

You have been doing this for so long, are you able to keep your professional and personal life separate, or have they been integrated?

So many of my good friends are from fencing, so a degree of separation is not possible, but I do think that as we’ve gotten older, everyone’s real lives have developed a lot, and we can all relate to each other in much broader ways. I would say it’s nearly impossible for those two things to be completely separate.

So, you go out for a couple of beers, do you aim to talk about something else, to give yourselves a break?

We try to talk about other things, but fencing always comes up.

What do you do for fun?

When I can, I love going to different places and experiencing different cultures. Africa has been unreal. I love traveling around the continent. But I also love trying different foods abroad.

And I love watching documentaries. I love photography. I spent a lot of time around the art world. Beyond that, I love speaking to people who love what they do and picking their brain. That’s just something that is fun for me.

What are you hoping to achieve this summer?

I don’t know if you know this, but I tore my achilles last March. It was a huge fight to come back, first of all, and I was back competing by October. I think most people were shocked that I was able to make it back in that time, but I missed half of the Olympic qualifications. I don’t even know how to answer that question, to be frank with you. The whole thing has been a big wrench thrown on a plan that was pretty thought out. I’ve never been injured before, I’ve never experienced this before. I’m grateful to be where I am today. This time last year I couldn’t walk.

I tore it 95% while I was competing at the world Cup; I was in the top eight. I felt that I was tired, but I thought: No you’re going to try to push, you’re going to try to do more! And I tried to do more, but then I heard a huge pop, and I just broke into tears. You know, when you asked earlier to tell you a story about how much I love this sport, I’ve never cried so hard over anything in my life, in front of so many of my competitors. I just broke down in tears and I had to be carried over by my teammates, because I was in tears — I didn’t know what the injury meant. So when I say that this sport is something I love to death, I’m definitely very sad about the way qualifications went this year, since I missed 50%. But I am proud that I’m back competing on a high level. It just may not be my time this time, but yeah. It’s just crazy that you’re positioned to go to the Olympics and then an injury like that happens. It’s just insane.

So, what was it like to pick up your gear for the first time post injury?

First of all, this recovery was miraculous. I tore my achilles on March 28th and started taking lessons late April with the boot on. And then I started fencing lightly, probably, in mid may. Not at 100%, obviously. I was just so happy to just be back on the strip and training. I felt like I saw another step to get back to competing. The first time I competed in a competition, I was scared. The day before the tournament, I was literally running sprints in a parking lot, because I just wanted to make sure I could run. I was testing to see if I could do the things I thought I could do. Because it’s very vulnerable to be back competing in front of people, who are dissecting every move that you’re making.

So, when you work with kids and you travel and share your experience, is this something you share?

A lot of kids have seen this up front. These kids saw me coming to their fencing class on a scooter to say hi to everyone. And they saw where I was a week before that, so a lot of them are able to contextualize what happened. But it’s definitely something that I share. It was definitely an experience.

Note* All images are provided by Daryl Homer and used with permission.