Through the Eyes of Maraini: Notable mentions of calligraphy from "Meeting With Japan" (19

- Liz Publika

- Jul 15, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 1, 2020

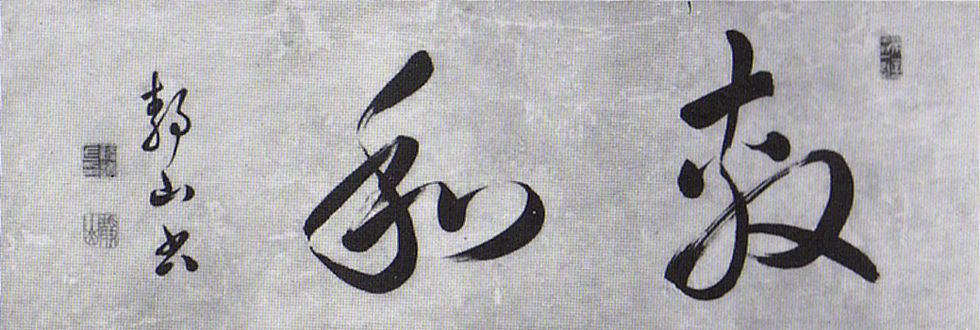

“In the Far East calligraphy is the mother of the arts.” — Fosco Maraini, in Meeting with Japan (1959)

Fosco Maraini (1912 — 2004) was a highly regarded Italian poet, lecturer, ethnologist, photographer, mountaineer, and travel writer, who had published a number of notable works that helped the West understand the customs and traditions of the East. Meeting With Japan (1959), perhaps his most famous work, was celebrated for its historical acuteness and enjoyable tone. Because it was widely translated and consumed by people around the world, a lot of what is known about Japanese culture had been popularized by him.

Maraini’s interest in different cultures was sparked by his parents, who were privileged enough to travel frequently along with their son. His early international experiences, couple with his innate ability to learn new languages — he was fluent in English, Japanese, and Tibeten — turned the young man into a cultivated, worldly, and curious individual with a passion for exploration. Eventually, it led Maraini to relocate to Japan, where he spent a considerable amount of time before returning to Italy.

“In 1938, after graduating in natural science at Florence University, Maraini won a scholarship that enabled him to take his family to Japan, where they settled on the northernmost island of Hokkaido,” writes The Guardian’s John Francis Lane. After the Italians and the allies singed an armistice in 1943, “the Japanese authorities demanded he sign an act of allegiance to Mussolini's puppet republic of Salo. Maraini refused, and was interned with his wife and three daughters in a concentration camp at Nagoya for two years.”

The experience was a stark departure from the life Maraini was accustomed to as a child, but his ability to see beyond class and live for the experiences instead of certain comforts allowed his appreciation for Japan’s culture and traditions to go unscathed. The family returned to Italy in 1947, and in 1953, Maraini briefly traveled to Tokyo. Meeting With Japan is, in part, inspired by this visit. His words and observations are as emotionally provoking as they are historically contextualized, and seem to resonate with a lot of people.

One of these observations in the book touches on the written word, and how the East approached it differently from the West. He summed it up like this:

“In our written language we are principally concerned with meaning and pronunciation. The quintessence of language is poetry, which approaches song, music; western poetry is composed essentially to be recited. But a language written ideographically is concerned with three things: meaning, sound, and appearance. When it ascends to poetry it tends to become rather the sister of painting or of architecture, the latter being understood as the art of spatial relations. Chinese poetry is written essentially to be seen; it penetrates to the mind by way of the eyes.”

Indeed, calligraphy is the art of beautiful writing. “In the Middle East and East Asia, calligraphy by long and exacting tradition is considered a major art, equal to sculpture or painting.” In many ways, this explains why “the accoutrements of brush writing were often created using the finest materials and craftsmanship." The essentials consist of paper, ink, an ink brush, an ink stick and ink stone. In Japanese culture, the set may also include an inkstone box, which is a stunning work of art in its own right.

“Inkstones were made of earthenware, porcelain, or stone that has a slightly abrasive surface to facilitate the grinding of solid inksticks (sumi) with water while preparing liquid ink. These solid inksticks are fashioned from soot (usually that of pine trees) and animal glue, and often scented with cloves or sandalwood. The dissolved ink accumulates in the well of the inkstone, and the calligrapher can control the density of the ink by adjusting the amount of water used and how long the inkstick is ground.”

The ink stick is the most valued piece of the puzzle, while other component wear out, one ink stick could be actively used for years, therefore a certain prestige is assigned to its history and contribution to the individual’s art. The process of preparing the ink, using the ink stick and the ink stone, is intended to be meditative. Because the ink is permanent, each stroke of the brush must be full of intention and purpose — but, at the same time, the ideograms

must flow naturally and freely.

“Ideograms, with their ancient history, are marvelous examples of abstract beauty, organisms of lines, of spaces filled and unfilled, of visible and invisible relations the sum-total of whose equilibrium is the result of the work of generations of artists,” writes Maraini “Every stroke of the brush has attained a perfect aesthetic functionalism within the whole. From this merely static point of view, its beauty is that of bones. A bone is function which has assumed form, form which has been turned into matter, limestone modeled by the ages.”

The art form embodies poetry, writing, painting, spiritualism, and personal expression. And on the art of calligraphy itself, perhaps Maraini says it best:

“Years of work and effort are required before true freedom can be attained in this art, before it becomes an intimate and personal means of expression. The results, however, are to be included among the great aesthetic attainments of mankind. I believe it possible to argue that the failure of Asia to develop an art of music comparable to that of the west was due to the fact that in the east the need for abstract beauty found full satisfaction in writing; the same satisfaction that Europe discovered in the harmony and orchestration of sound.”